When weather is dangerous, or rescues are needed, the university’s leading-edge monitoring, forecasting and warning systems keep NYC, the Coast Guard and coastal communities alerted

Bad-weather events and ongoing climate change are a big deal.

Last year, in the U.S. alone, the combined toll of all extreme-weather events was hundreds of lives and nearly $100 billion — and the 28 worst weather events caused property damage of more than $1 billion each. The warming climate leads to more severe storms and, in turn, increased danger from storm surge and flooding.

Stevens Institute of Technology is racing to the rescue.

To build more resilient communities, Stevens researchers have developed one of the most advanced ensemble-based flood advisory systems in the nation to warn communities of impending flash flooding and storm surges.

Supported by funding from the U.S. Department of Education, the State of New Jersey and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ), among others, these systems play a crucial role in saving lives and reducing economic losses.

“We’re the only entity that uses perturbations of European, Canadian and U.S. weather models plus real-time observations to continuously provide four-day predictions of storm-surge levels along the New Jersey and New York coasts,” explains Muhammad Hajj, director of Stevens’ Davidson Lab, which maintains the systems.

“Our tools and street-level predictions are unmatchable and uniquely valuable.”

Life-saving accuracy for Sandy, ‘Sully’ and more

As October 2012’s Hurricane Sandy barreled down on the U.S. East Coast, about to take a sudden turn directly at the New York metropolitan area, Stevens was there with advance warnings and predictions.

University scientists went wall-to-wall on media outlets, warning the region and nation that this generational storm would bring tremendous flooding, record high waters and untold storm-surge damage.

“Three to nine feet higher,” predicted Stevens researcher Philip Orton on live television, 12 hours before high winds and tidal surges arrived. “That’s on the conservative side. There’s a good chance large areas will go off the [power] grid. The subways are going to get flooded. This isn’t like rain flooding. This is an ocean of water getting into your basement apartment.”

“People need to get to high ground.”

Those warnings — powered by the Stevens Flood Advisory System (SFAS) — proved extremely accurate when the devastating storm eventually wreaked $20 billion in damage in New York City alone. That system remains required reading for local planning and emergency-management officials.

“Most days, SFAS is the first piece of information I check in the morning,” notes Caleb Stratton, the city of Hoboken’s Chief Resilience Officer.

As a part of the advisory system, Stevens also continuously tracks the region’s notoriously swift, complex and often dangerous ocean and river currents. When a US Airways jet went down in New York’s Hudson River in 2009, the U.S. Coast Guard turned immediately to Stevens to determine how to secure and move the disabled aircraft as it quickly drifted south toward the open ocean.

And when a helicopter and light plane collided over the river later that year, Stevens researchers again helped investigators precisely locate, search and recover wreckage on the deep, murky river bottom.

"The contribution and professionalism of the men and women of Stevens who assisted our team during the initial hours and days after the accident were critical,” said Deborah Hersman, then-chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board.

When boats are lost or adrift offshore, or passengers have gone overboard, Stevens is once again a primary emergency resource: Its predictions are tapped more than 1,000 times each year by the U.S. Coast Guard’s search and rescue operations.

“[Stevens’] model remains our only consistently reliable model for one of the busiest maritime environments in the nation,” notes Commander Matthew Mitchell, policy chief for the Coast Guard’s Office of Search and Rescue.

“It was used in more than 300 search and rescue responses in the last 12 months, saving or assisting [in saving] nearly 700 lives.”

Computation, communication are key

To do it, Stevens uses proprietary computer simulations — and a team of experienced researchers.

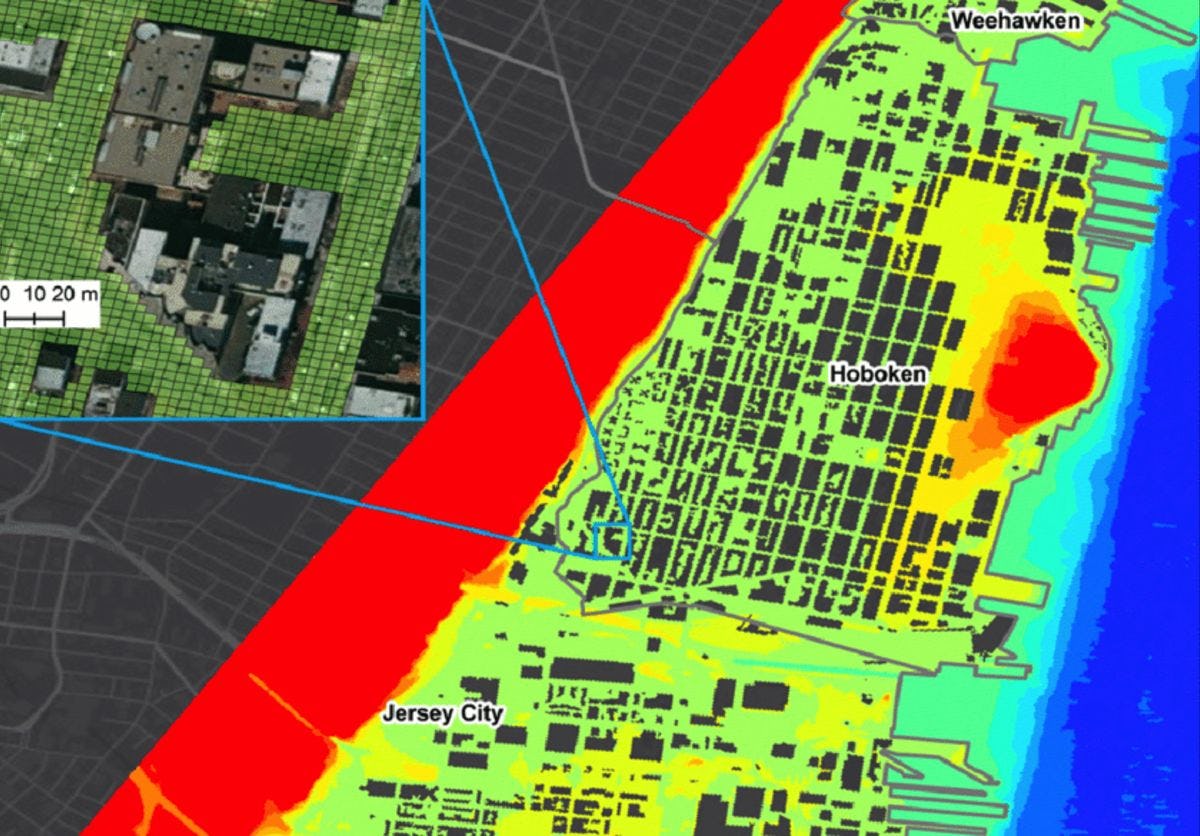

Stevens launched its first observation system, known as NYHOPS, in 2004 after placing sophisticated sensors and weather stations at various points around New York Harbor, Newark Bay and in the Hudson and East rivers. That data was fed into computational models co-developed with Princeton University, producing reliable reports of changing salinity, turbulence, wave height and more.

Three years later, the university added new models to the mix, rolling out the SFAS to forecast accurately how high the Atlantic and its estuarine rivers could rise during hurricanes, winter storms and heavy rains.

The two systems, whose models and algorithms are periodically updated, are now powered by more than 200 sensors and draw on leading weather models to calculate regional wind, ocean, river and flood dynamics.

“The models begin by making intelligent predictions about deep-ocean dynamics based on weather conditions, then move to calculating specific dynamics in coastal areas,” explains Hajj. “It then factors in hydrologic model calculations in areas impacted by rivers, such as New York Harbor and major river drainages of New Jersey, to generate its predictions.”

All this information is communicated — quickly — to local authorities during crises. For example, Hajj and Orton often join PANYNJ’s emergency-management calls when strong storms or heavy rains are predicted to move in and impact the area. During maritime emergencies, the Coast Guard pulls surface-current data from NYHOPS to inform searches and rescues.

“Davidson Lab provides us tactical information on the risk of coastal flooding that we use for decision-making and hazardous-weather preparations,” says Sal Kojak, a director in PANY/NJ’s emergency management unit.

“This partnership enhances our situational awareness so we can issue alerts, prepare for coastal flooding and mitigate losses.”

Stevens also works very closely with urban and coastal communities, including New York City, to predict and defend against an equally formidable challenge: climate-change effects such as sea-level rise, which is gradually consuming coastal properties and increasingly pushing parts of the Big Apple underwater.

“There are parts of Queens, near Kennedy Airport, that flood 60 times a year,” explains Orton, who has long advised the city’s mayors on climate change and local flood risk. “This will only become worse in the decades to come, because the sea is rising one to six feet per century, mainly due to global warming and ice-cap melting. And the rate of that rising is accelerating.

“Flood hazards are growing, and the time to prepare is right now,” concludes Hajj. “For that, we will be expanding the SFAS’ capabilities to cover additional vulnerable communities.”