As An Especially Worrying 2024 Hurricane Season Kicks Off, Stevens Supplies Forecasts, Offers Insights

Researchers discuss hurricanes, floods, storm surges, climate change, emergency preparedness

As the annual Atlantic-basin hurricane season kicks off, it’s worth noting that last year’s season was expected to be mild — but it turned out to be far more active than predicted, producing 20 named storms, the fourth-most since 1950 (when naming began).

Only a year earlier, Hurricane Ian rocked the Caribbean and Florida, one of the most powerful hurricanes ever to make landfall in the U.S. More than 160 people died; and estimated damages from the system topped $110 billion.

This summer? It could be even worse. In a so-called La Nina year and amidst record-warm ocean temperatures, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is forecasting an extremely active and stormy summer.

“There’s been a big relative jump in both ocean temperature and mean sea-level over the past year,” notes Stevens researcher Philip Orton, one of several Davidson Lab faculty who studies ocean conditions, flooding, extreme weather and climate change.

“That’s probably bad news for this region and others on the East Coast with regard to strong storms and extreme rainfall and flood events.”

Active season, threats on the way

Indeed, NOAA forecasts from 17 to 25 named storms occurring in the Atlantic basin between June 1 and November 30, including potential for eight to 13 hurricanes and four to seven major hurricanes like Ian (which pack winds of 111 miles per hour or higher).

Stevens research has previously demonstrated that communication peaks just before or during a hurricane's strike. So it's important to be prepared. That’s why experts in the university's Davidson Laboratory continually model and forecast extreme weather events: to supply relevant agencies and communities with data, helping warn the public of flood and surge events associated with hurricanes or large storms as many as four days in advance.

“Most days, the first piece of information I check in the morning,” says Caleb Stratton, chief resilience officer for the city of Hoboken, of the Stevens Flood Advisory and NYHOPS systems, two free online monitoring and forecasting tools.

Media outlets also frequently tap Stevens' expertise, including during last winter's heavy California rains and flooding, and during both Hurricane Sandy and Hurricane Harvey. And the university supplies the Coast Guard, New York City, New Jersey Transit; and the National Weather Service and other partner agencies with data, as well.

Orton, a longstanding member of the New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC), has produced research showing how monthly flooding could spread from a few low-lying areas of southern Queens to several other areas around the city over the next 30-60 years.

“We are talking about flooded streets, homes, high-traffic expressways and boulevards, subways,” he explains. “The infrastructure of the city was not engineered to factor in either the sea rising or rain intensifying, and will require adaptation or protection.”

Reza Marsooli, another Davidson Lab researcher, models river and coastal flooding, storm surges and wave hazards during periods of changing climate.

With approximately 95 million Americans — nearly one-third of the U.S. population — residing in coastal regions, his work supplies the nation's cities and communities with key intelligence as planners work to build both physical defenses and emergency response plans.

Marsooli has published findings, for instance, concluding New York's Jamaica Bay will soon begin flooding much more frequently.

“The framework we used for this study can also be replicated," he notes, "to demonstrate how flooding in other regions will look by the end of the century, which will help mitigate risk and better protect communities.”

Extreme Weather FAQs with Philip Orton & Reza Marsooli

Q: Is the weather becoming more extreme?

A: Yes. A host of recent studies worldwide have confirmed that summers are indeed becoming hotter and rainier; storms are becoming stronger; and floods are becoming more frequent and stronger.

Q: Why is this happening?

A: The Earth’s base temperature has warmed by almost two degrees Fahrenheit during the past century alone. That doesn’t sound like much, but it has already been enough to melt and unlock huge quantities of glacial ice at Greenland, Antarctica and other locations.

All this extra meltwater empties directly into the world’s oceans, where it slowly rises against continents and islands. This sea-level rise, driven by a warming and expanding ocean, is one of the primary challenges created by global warming.

The warming atmosphere and ocean also produce increased tropical-region heat and humidity, which help birth and strengthen destructive storm systems such as hurricanes.

Stevens research recently published in the scientific journal Nature Communications has demonstrated how major regional hurricanes like Hurricane Sandy are significantly worsened by the human-driven effects of climate change. In the case of Sandy, the damage is estimated to have been perhaps $8 billion in total.

Q: How will this affect those living near coastlines?

A: If you live in a low-lying coastal area that occasionally flooded during storms in the past, prepare for much more frequent floods.

Coastal areas along the entire Eastern Seaboard of the United States — from Florida to New England — will experience higher coastal flooding during storms in the near future. One study co-authored by Stevens researchers confirms that hurricane-induced flooding will continue to become more severe along both the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf coasts over time due to the effects of climate change.

Q: How is Stevens helping prepare the tri-state region and the nation for hurricanes, storms and flood events?

A: Physical defenses and warning systems are regularly discussed, planned and tested in the Davidson Laboratory.

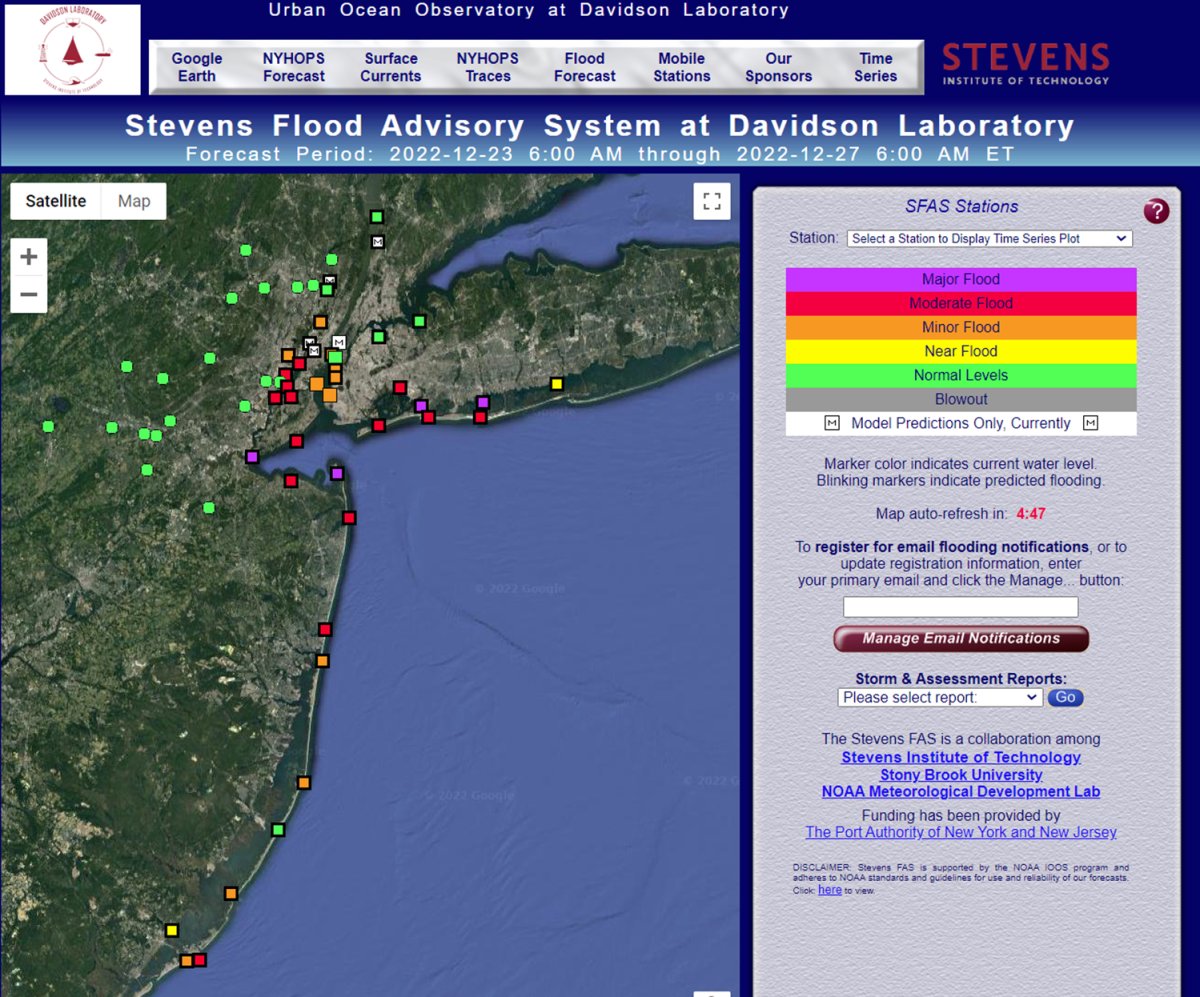

The Stevens Flood Advisory System (SFAS), a free real-time resource accessible to the public, produces four-day advance flood forecasts for the New Jersey and Metro New York coastal region. Not only does SFAS provide a central forecast, but it also shows the uncertainty in a given forecast, helping to convey the potential high-end (worst-case) consequences.

Stevens has also operated the New Jersey Coastal Protection Technical Assistance Service since 1992, supporting efforts to cope with beach loss during strong storms. The university produces research on innovative approaches and technologies to protecting the coast such as so-called 'living shorelines' of natural materials including oyster reefs and coastal plantings.

Q: Do Stevens students also contribute to the university's resiliency work?

A: Yes. Stevens undergraduate and graduate students regularly participate in Stevens’ storm-surge modeling and adaptation research; conduct field research on beach replenishment along the Jersey Shore during summer; predict the effects of hurricane-induced coastal erosion; and engineer novel, more resilient types of natural defenses (such as plantings) and architecture capable of withstanding stronger storms, including the award-winning SU+RE House, which took top prize first in the Department of Energy’s Solar Decathlon.

Learn more about Stevens' life-saving urban and coastal resiliency research at stevens.edu/resilience.